British diplomat Simon Shercliff was appointed as ambassador to Iran earlier this month. He seemed to be off to a great start: he had already spent three years in Iran, from 2000 to 2003, all the time when reformist President Mohammad Khatami was in power. Things seemed more hopeful for the country in general, and Western diplomats had more wide-ranging relations with civil society. Shercliff had thus learnt Persian, and he was fluent enough to announce his arrival in a minute-long video clip posted on Twitter on August 10. It earned 1,400 likes and almost 300 retweets, while dozens congratulated Shercliff on his grasp of Persian and wished him well.

Then, all hell broke loose.

Just a day later, Shercliff was subject of a tweet that went viral in all the wrong ways. Together with Russian ambassador Levan Dzhagaryan, he had engaged in a bit of historical reenactment that led to a photo tweeted out by the Russian embassy in Tehran. Meeting in the courtyard of the Russian embassy building, Dzhagaryan and Shercliff posed on the historic staircase that was the site of one of the most iconic events in the history of the 20th century: the Tehran Conference of 1943.

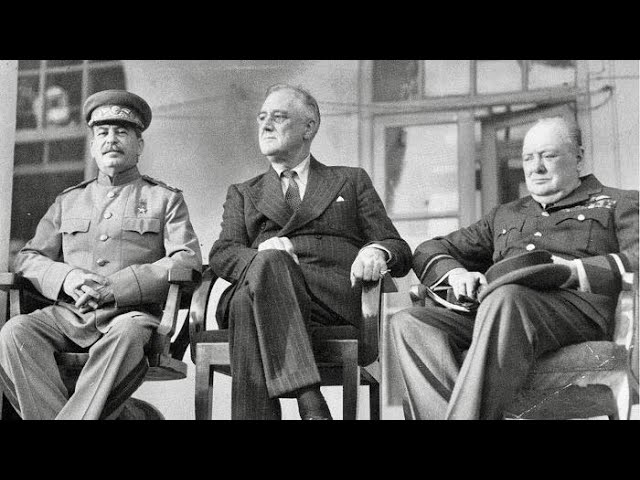

From November 28 to December 1 that year, the leaders of the three main Allied countries had convened in what was then the Soviet embassy to map out the fight against the Nazi Germany. Britain’s Winston Churchill had separately met with both US President Franklin Roosevelt and Soviet leader Joseph Stalin before. But Tehran was the first place the Big Three met in person.

Almost 78 years later, Shercliff and Dzhagaryan staged a homage to the meeting by sitting on two chairs on the same balcony, in the exact same positions as had been captured in a famous photo of the conference. They even left a chair empty for the Americans, who have had no diplomatic presence in Iran since the 1979 Islamic Revolution, after which the US embassy hostage crisis led to the severing of all official ties.

To an outsider, it might not be immediately clear why so many Iranians from across the political spectrum took offense to this photo. But the offense was indeed wide-ranging. The outgoing foreign minister, Javad Zarif, tweeted: “I saw an extremely inappropriate picture today. Need I remind all that Aug. 2021 is neither Aug. 1941 nor Dec. 1943.”

Not to be left behind, the conservative Iranian parliament speaker Mohammad Bagher Ghalibaf called on Dzhagaryan and Shercliff to apologize – “otherwise, swift diplomatic action will be necessary.”

Even ordinary Iranians, and Iranians with anti-regime sympathies, posted their own angry responses. Some wondered aloud whether the Russians were already feeling more confident after the inauguration of hardline anti-West president Ebrahim Raisi earlier this week.

Zarif’s allusion to August 1941 gives a clue as to why some Iranians were so upset. It was on this date day that combined forces of Britain and the Soviet Union invaded the then-neutral Iran. Shortly afterward on September 16, 1941 its monarch, Reza Pahlavi, was deposed and replaced by his young son, Mohammadreza Shah. From the perspective of many Iranians, the picture was a symbol of two hated superpowers once again determining the course of events in Iran.

At the time, Britain and Russia were not just global heavyweights, but Iran’s neighbors. The vast Russian empire bordered Iran to the north; in the early 19th century, it had annexed the southern Caucasus following a series of wars. To the east, the British ruled India and had repeatedly attempted to invade Afghanistan. While Iran is one of few countries in history to have never been formally colonized, it was repeatedly humiliated and pushed around by Russia and Britain, both of which also controlled much of Iranian politics through secret back-channels and client relationships.

This long tradition has left a permanent mark on the Iranian psyche, whereby grand powers are often assumed to be beyond events large and small. The same topic gave fodder to the Iranian satirist Iraj Pezeshkzad, whose novel-turned-TV series My Uncle Napoleon mocks this tendency toward conspiratorial thinking. The catchphrase of the book’s titular character, Uncle Napoleon, has now become a common Iranian saying to refer to events with unknown origins: “It must be the British!”

Iranians also remember Russia’s role in suppressing the democratic Constitutional Revolution of 1906 to 1911, during which the forces of Tsarist autocracy invaded Iran and later gave refuge to anti-parliamentary Qajar tyrant Mohammad Ali Shah. More than 100 years later, the political support that Russia’s President Vladimir Putin often extends to the Islamic Republic is viewed by many Iranians in the same light.

In response to the tweet on Wednesday, many Iranians also made cheeky references to Alexander Griboyedov, a Russian diplomat in Iran who was murdered in Tehran, along with some of his staff, by a mob in 1829. Griboyedov had played a key role in the 1828 Treaty of Turkmenchay, which forced Iran to cede control of South Caucasus.

What Actually Happened at the Tehran Conference?

Frankly, if you ask this author, Iranians have many reasons to be proud of the Tehran Conference. It played a vital role in global contemporary history, and in fate of humanity. It was right here that Roosevelt and Churchill finally gave Stalin the promise he’d been waiting for: they’d open a new front against Nazi Germany in Western Europe to relieve pressure on the Soviets who, a few months before, had achieved a monumental victory over the Germans by winning the Battle of Stalingrad.

Had the forces of Adolf Hitler been able to seize Stalingrad and pave their way to the oil wells of Baku, the outcome of the war could have been different. Instead the Red Army’s destruction of the German Sixth Army turned a page. The victory was greeted with joy across the world, including in Iran, where it was cheered on by both liberals and the supporters of the communist party (Tudeh), which saw its membership swell as a result.

Control of Iran by the Allied forces was also crucial to the victory over the Nazis. It was through the so-called “Persian Corridor” linking Iran to Soviet Azerbaijan that much of British and American aid made it to the Red Army. About 50 percent of all supplies the US Lend-Lease program gave to Soviet Union passed through Iran. These shipments from the US and UK would circle round the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa and come all the way to the port of Bushehr on the Persian Gulf, then travel across Iran by road before they made it to the Soviets by land or over the Caspian Sea. Other resources were moved up by the railways recently built by Reza Shah (themselves the subject of an amazing new book by historian Mikiya Koyagi).

There was thus something poetic to Tehran hosting the first-ever meeting of the Big Three, in which all parties could finally be in a relatively good mood after having put the Nazis on the retreat. Even though Iran was occupied, the Allies promised to respect its sovereignty and it was never cut off or annexed. In no small part this is owed to the hard work of Iranian diplomats at the time.

This, in turn, is why a seasoned diplomatic historian of Iran has said the Tehran Conference should be a “source of pride” for Iranians. “Iranians should be proud of the fact that skillful Iranian diplomacy extracted an Allied commitment to Iran’s sovereignty and territorial integrity, at a time when they had little or no leverage over the occupying powers,” Roham Alvandi, a professor of international history at LSE, told IranWire.

Roosevelt and Churchill stayed true to their main promise. Six months after Tehran, Allied forces landed on the beaches of Normandy in northern France and initiated the liberation of Western Europe. In less than a year, on April 25, 1945, Soviet and American troops, coming from opposite directions, met at the Elbe River on German territory. On its way to Berlin, the Red Army had liberated the Auschwitz concentration camp on January 27, an event which is commemorated to this day as International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

The unity of Soviets with their Atlantic allies had ushered in what the British Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm called the Grand Alliance: a global anti-fascist coalition that helped save human civilization as we know it. Whle the war was raging, this alliance had perhaps no bigger fan that Earl Browder, leader of the Communist Party of the United States, who was as ardent a communist as he was an American patriot, and whose party’s flag was emblazoned with pictures of both Karl Marx and Abraham Lincoln. In a pamphlet he wrote in 1944, Browder had a name for this unique political orientation that championed Soviet-American unity: “the spirit of Teheran” (using a common English spelling of the city at the time).

“The time is over-ripe for America to… proceed to gather the rich fruits of foresight, boldness, and energy in spreading the spirit of Teheran to the four corners of the world,” Browder wrote in the pamphlet Teheran: Our Path in War and Peace, which was published in New York.

The spirit sadly didn’t last long, as the Grand Alliance crumbled soon after the Nazi defeat with the onset of the Cold War. Stalin, one of the greatest criminals in recent history, was never going to be a stable partner. And it was, again, Iran that became the locus of this stagnation. It was the refusal of the Soviet soldiers to leave Iranian territory after the war that led to the first-ever resolutions of the nascent United Nations Security Council, and one of the first post-war confrontations between the Soviets and the Americans.

The promises of the Tehran Conference of 1943 had played a key role in securing Iran’s sovereignty after the war. “The 1943 Tehran Declaration and the earlier 1942 Tripartite agreement were not just diplomatic niceties,” says Alvandi. “They were crucial to ending the Soviet occupation in 1946 and securing post-war aid in recognition of Iran’s contribution to the war effort.”

This week, in response to Photo-gate, the Russian embassy tweeted something of a non-apology: “Taking into account the ambiguous reaction to our photograph, we would like to note that it does not have an anti-Iranian context,” it said. “We are not going to offend the feelings of the friendly Iranian people. The only meaning that this photo has is to pay tribute to the joint efforts of the allied states against Nazism during the second world war. Iran is our neighbour and friend, and we will continue to strengthen relations based on mutual respect.”

Simon Shercliff, who had never shared the original picture, simply retweeted the Russian response.

But the discussion amongst Iranians will continue. Some pro-regime hacks have already posted a picture of Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei meeting with Putin to compare it with the Shah not having been in the famed pictures of the Big Three. Of course, one could have countered this with a picture of young Shah meeting Roosevelt on the sidelines of the Tehran Conference, signifying the respect the latter held for Iranian sovereignty.

Indeed, for many Iranians, the most insulting thing in the picture might have been the empty chair in between the diplomats: a reminder of how the rulers of Iran have practiced a demagogic anti-Americanism that has made Iran only more dependent in turn on other foreign powers, such as Russia and China.

“For forty years, Iran is proud of that empty chair,” Iranian socialist activist Goudarz Eghtedari wrote in a Facebook post. “But the price of this is paid by the people, whose progress, development and future has been frozen for no reason.”

As the Islamic Republic has made Iran into a global pariah, Iranians continue to cherish the dream of an independent and sovereign homeland.