Co-written with Didi Tal for IranWire

In their attempt to reconstruct the past, historians often rely on archival documents. But these documents never tell the full story and we often have to work through the gaps. Looking at some of the major archives related to the Holocaust, we sifted through official documents, lists, registrations, and papers about individuals who were in Germany or its occupied territories during or immediately after the war to answer a basic question: In what ways were Iranian citizens entangled with Holocaust history? Who were some of the Iranians who ended up in Nazi concentration camps and other sites related to the Holocaust?

Our most important resource was The Arolsen Archives, located in Bad Arolsen, Germany, and accessed through the US Holocaust Memorial Museum. Formerly called the International Tracing Service archive (ITS), these archives were opened for research in 2007.

The collection contains more than 200 million digital images of documentation on millions of victims of Nazism—people arrested, deported, killed, put to forced labor and slave labor, or displaced from their homes and unable to return at the end of the war. These victims include at least 44 Iranians.

The fates of these Iranians were diverse: some were students who came to study in Germany or another European country before or during the war; some might have been workers in German industry, though it is likelier that they were forced laborers; a few were undoubtedly victims of Nazism and were arrested, imprisoned, or detained in concentration camps.

Most of these individuals were not Jewish but they came from a variety of religious and ethnic backgrounds: Azeri, Armenian, Christian, Muslim, Baha’i. Many of the people only appear as names on official lists–hospitalization records, displaced person (DP) camp counts, and censuses of the foreign nationals living in various occupation zones shortly after 1945.

Of others we only know from search inquiries of relatives who tried to find their loved ones in the postwar chaos. While we’re not always able to reconstruct the details that are missing from the paper trails, we do know that those Iranians who were in Europe during the war, were deeply affected by this history.

Even though they might appear to be just piles upon piles of paperwork, the archives reveal the human side of history, and tell stories about resistance, migration, love, and death. Here, we note some examples of Iranian individuals who found themselves in Nazi concentration camps or were otherwise victims of the war and its vicissitudes.

Aga Hassan’s journey stretches across physical and historical grounds, and sheds light on what Iranian victims of Nazism endured. He was born in 1916 in Khoy, an Azeri-majority city in northwestern Iran and worked in the same city as a typographer.

In 1941, as Iran was occupied by Britain and the Soviet Union, Khoy fell to the latter. The occupying Soviet forces demanded manpower from the Iranian authorities and Aga Hassan was among those deported to the USSR. Together with about 200 others, he became a forced laborer in a port in Crimea, then part of Soviet Russia. His conditions took a turn for the worst when Crimea fell to Nazi Germany in July 1942, after an eight month campaign, aided by Germany’s allies, Romania and Italy.

Many Soviets were taken as POWs and Hassan and other laborers were sent to the Nazi-run concentration camp Majdanek in German occupied Poland. Some in Hassan’s group were killed in the camp as, according to his testimony, the Germans mixed up non-Jewish Iranians with the Jewish prisoners who were being killed on a mass scale. But Hassan survived. From Majdanek, he was transported several times to different camps in occupied Poland, Germany, and Austria as a forced laborer.

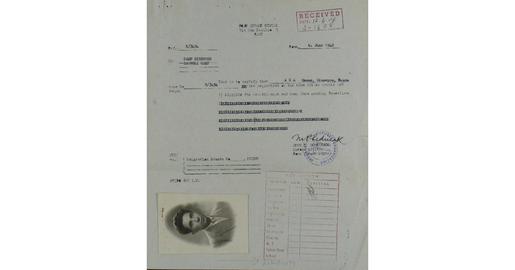

Aga Hassan’s documents from a DP camp in Italy are found in the Arolsen Archives

In April 1945, just as the war was coming to an end, he escaped over the Italian border during an air raid, and arrived in the Udine DP camp, now under British control. From there, Hassan moved to Rome, where he sold cigarettes on the black market, married an Italian woman, and had a daughter. In his application for assistance from the Preparatory Commission for the International Refugee Organization (PCIRO), he asks to be allowed to settle in Turkey with his family. For whatever reason, he didn’t want to return to Iran. It seems that his request was denied.

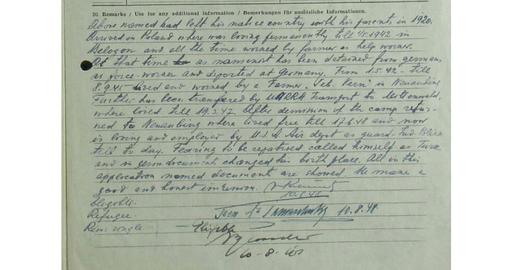

Another forced laborer who applied for assistance was Toboj Magammed. His testimony was recorded on the PCIRO application form

Above named had left his native country with his parents in 1920. Arrived in Poland and here was living permanently until 1.5.1942 in Selogon and all the time worked by a farmer as a help worker.

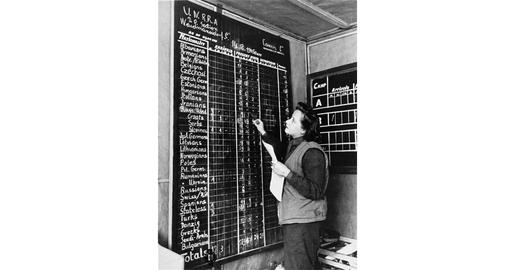

On a large blackboard an UNRRA official tallies the numbers and nationalities of displaced persons in camps in the Wardmanndorf area. There were 11 Iranian displaced persons in the camps at the time. Klagenfurt, Austria. December, 1945.

Forced labor is one of the recurring themes of the archives. Some Iranians, like Hassan, were brought into Soviet occupation zones directly from Iran, and from there to German territories.

Others, like Magammed, were already in Europe or even Germany itself as workers or students, and became forced laborers under Nazi rule. While many of the documents tell little about individual stories and fates, they often point to companies and organizations that were part of the Nazi operation, many of which exist till today, like Siemens and Demag.

Those companies notoriously used forced labor to their benefit during the war, and while it’s impossible to say how an Armenian man from Iran’s Tabriz, Aghbekian Hartoun, found his way to Germany during WWII, it’s safe to assume that he ended up as a forced laborer since his name appears in records of Organisation Todt, a civil engineering organization run by Nazis that folded in 1945.

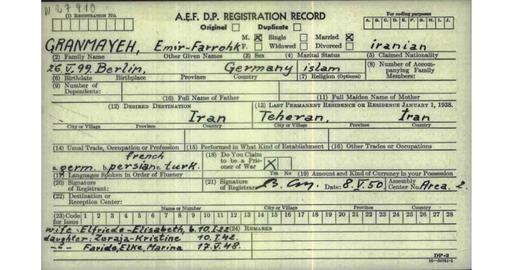

Some other victims are thought to have been involved in anti-Nazi activity. Emir Farrokh Granmayeh was born in Berlin, the son of the Iranian ambassador to Germany, Reza Moayed al-Saltanah. He grew up and lived in between Germany and Iran. By the 1940s, he was married to a German woman and had a family in Berlin.

In his postwar application for assistance by the PCIRO to be repatriated to Iran, he describes himself as a Prisoner of War. During the war, Nazi Germany attempted to use prominent Iranians in Berlin as part of its efforts to broadcast propaganda to Iran. Some notable figures were successfully recruited for this effort including Bahram Shahrokh, son of a prominent Iranian MP and head of the Zoroastrian community in Iran, who became the main Persian voice of Radio Berlin.

The Nazis wanted Granmayeh to also join these efforts but he refused and had to pay a high price for his refusal. In 1944, he was sent to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp. Granmayeh deserves to be remembered as a case of a hitherto little-known story: an Iranian who braved political opposition to the Nazis and thus found himself in a concentration camp.

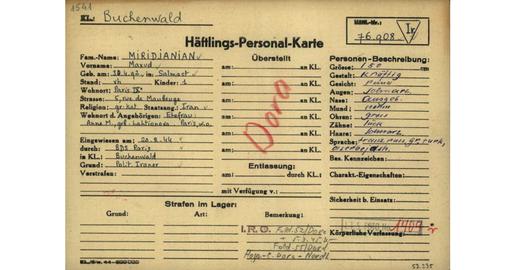

We don’t know much about the reason why Maxud Miridzianian, an Iranian innkeeper living in Paris, was sent to Buchenwald and Mittelbau Dora. His Häftligs-Personal-Karte–prisoner ID–from the concentration camps list him as an Iranian political prisoner.

Many Iranians of the time were partisans of socialist, communist or other anti-fascist tendencies that would have deemed them politically unacceptable to the Nazis. He did not survive to tell his story, and died in the concentration camp Nordhausen in March 1945, just a month before it was liberated by American forces.

Others who may have been active against the Nazi regime possibly worked for other states or organizations: Ayron Mohamed was arrested in 1943 in Berlin for suspected espionage. He was a police president. In his arrest documents he is described as being armed, well dressed and having a tattoo of a woman’s face on his arm.

He was detained in the concentration camp Oranienburg; a police prison in Berlin, Zell am See; and another police prison in Salzburg. He was still alive during the liberation of his prison in Berlin by the US army in 1945, but died the same year in Bern, Switzerland.

This man is a rather curious case because his name bears a striking resemblance to Mohammad Hossein Ayrom who was also a police chief but who is known to have died in 1948 in Liechtenstein. Is it possible that this is the same well-known Ayrom or a relative of his?

Another person who may fit this category is Afshar Abolsofl whose story is possibly the strangest of all. Here, we can see how hard it can be to tell where the historical truth lies. His story is in many ways also the story of the archives themselves and of documentation and its consequences.

For years after the end of the war, at least up until 1959, Afshar Abolsofl tried to lay his hands on his arrest protocols by the Gestapo. He needed them in order to claim reparations from the German government and restart a decent life after losing everything that he had.

According to his testimonies, Abilsofl served as a spy during the war, working for Switzerland. In this work, he “betrayed his country people,” according to him, though the nature of his service remains in large part a mystery. One detail that is mentioned in his correspondences is that he was tasked with gathering information on an Iranian Jewish man named Haim Askenassi.

Askenassi lived in Paris, was detained in the internment camp Drancy, and then deported to Auschwitz where he died. But Abolsofal was not able to track him down during the war. He himself was arrested by the Gestapo in Berlin, and according to him, rescued by the Swiss government and so evaded imprisonment. The many letters Abolsofl writes after the war lead to a dead end.

The German authorities are not able to find proof for his detention by the Gestapo, and his attempts to get reparations remain fruitless. But his correspondences contain more than just his vague story. The Germans are able to find arrest documents of a different person with a slightly similar name, a man named Afschar Abdul Ali Khan who was in fact arrested by the Gestapo for suspected espionage and then deported from Germany.

The similarity is striking, but Abolsofl insists that he is a different person, and that he too was detained by the Gestapo in Berlin for his political activity. The evidence is not found, and reparations cannot be claimed, but this story still carries important information about the presence and involvement of Iranians during the Holocaust. We can see that there were others, like Haim Eskenassi and Afschar Adbul Ali Kahn, who are at the margins of Afshar Abolsofl’s history, who were affected by this history, but did not leave a paper trail behind them.

Stories such as those of the individuals above reminds us that the Holocaust, i.e. the systematic murder of six million Jews by Nazi Germany and its collaborators, also left its marks on other nations, including Iran: whether through the Iranians who were persecuted by the Nazis due to their politics or to those who simply found themselves victims of the adverse conditions of the Second World War. Much more research needs to be done to achieve a fuller picture.

Most crucially, we must add the above stories to that of those; as well as those who are likely to have been killed in the Holocaust. Showing all the different ways in which Holocaust history intersects with histories of various nations, like Iran, can be an effective way to engage new generations with this horrific crime and its enduring lessons.

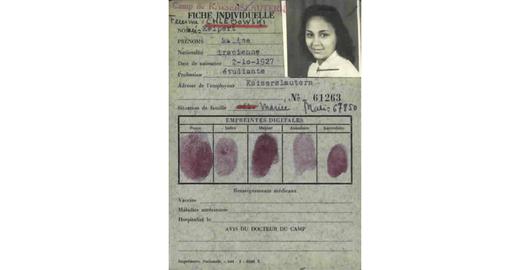

Tuba Kuipert, an Iranian Baha’i, found herself in Kaiserslautern DP camp in Germany after the war.